The post-war era Britain’s population was faced with massive housing shortages. The existing housing stock was often disgracefully inadequate for even the most basic of needs. Modernist architecture with its close links to left wing ideology reflected a progressive solution to the practical and social issues of the time. At its height in the 1950s Social Housing was unquestionably a central pillar of Britain’s regeneration following the devastation of the Second World War. Modern, and affordable, it represented an advancement in society; where the working classes were for the first time given the opportunity to live in a decent home. These projects and buildings were often striking exercises, bold and futuristic in their character and breathtaking in the scale of their ambition. Of course not everything proposed and executed by the town planners was to be warmly received. The high level philosophy and design of Corbusier was all too frequently brought crashing down to earth by the constraints of both economy and ability. Despite the misgivings, the new house or flat on the estate offered to millions the promise of a new beginning; a chance of escape from the almost medieval squalor endured by working class families through generations since time immemorial. But this wasn’t only about a specific part of the demographic. Social Housing was intended for all, to encourage the integration of different echelons of society. As late as the mid 1970s you would find a wide range of people living on these estates. Our home was in a tower block in Sheffield’s Norfolk Park. My father was a skilled tradesman, our neighbour a teacher: the commonality shared by the occupants of these developments was that of employment. These places were on the whole very positive places to live in, vibrant and open with a strong sense of community. However by as quickly as 1979 the political landscape in our country had changed forever.

Our leaders decided that talk of society was no longer valid, the interests of the individual reigned supreme and through the Right To Buy scheme we were encouraged to take part in the dismantling of this great social project. Those who could took advantage of the schemes. The theory was straightforward enough. If you give people the opportunity to own something themselves then they will take greater care of it than the state ever could. Their emotional connection to their homes will be stronger. Individuals will be empowered, less docile more entrepreneurial, all will benefit. Within a decade most of the new property owners had sold up and moved on. Who was left behind? And what did it mean to be there? A council tenancy now carried with it a sense of failure and increasingly blame. Within the upwardly mobile 80’s paradigm it’s your own fault if you are poor, isn’t it? Beyond the physical our psychological relationship towards these estates and buildings was quickly and profoundly altered. Far from being symbols of hope and egalitarianism, estates became places to avoid.

The notoriety increased exponentially through the 1980s and 1990s. Names such as Moss Side or Red Road taking on almost mythic proportions, becoming as much feared and despised as the very slums and tenements which they replaced. The rampant excesses of the housing market in the late 1990s, which lead to an Englishman’s home becoming not only his castle but also his retirement fund, all but finished the job started almost thirty years earlier.

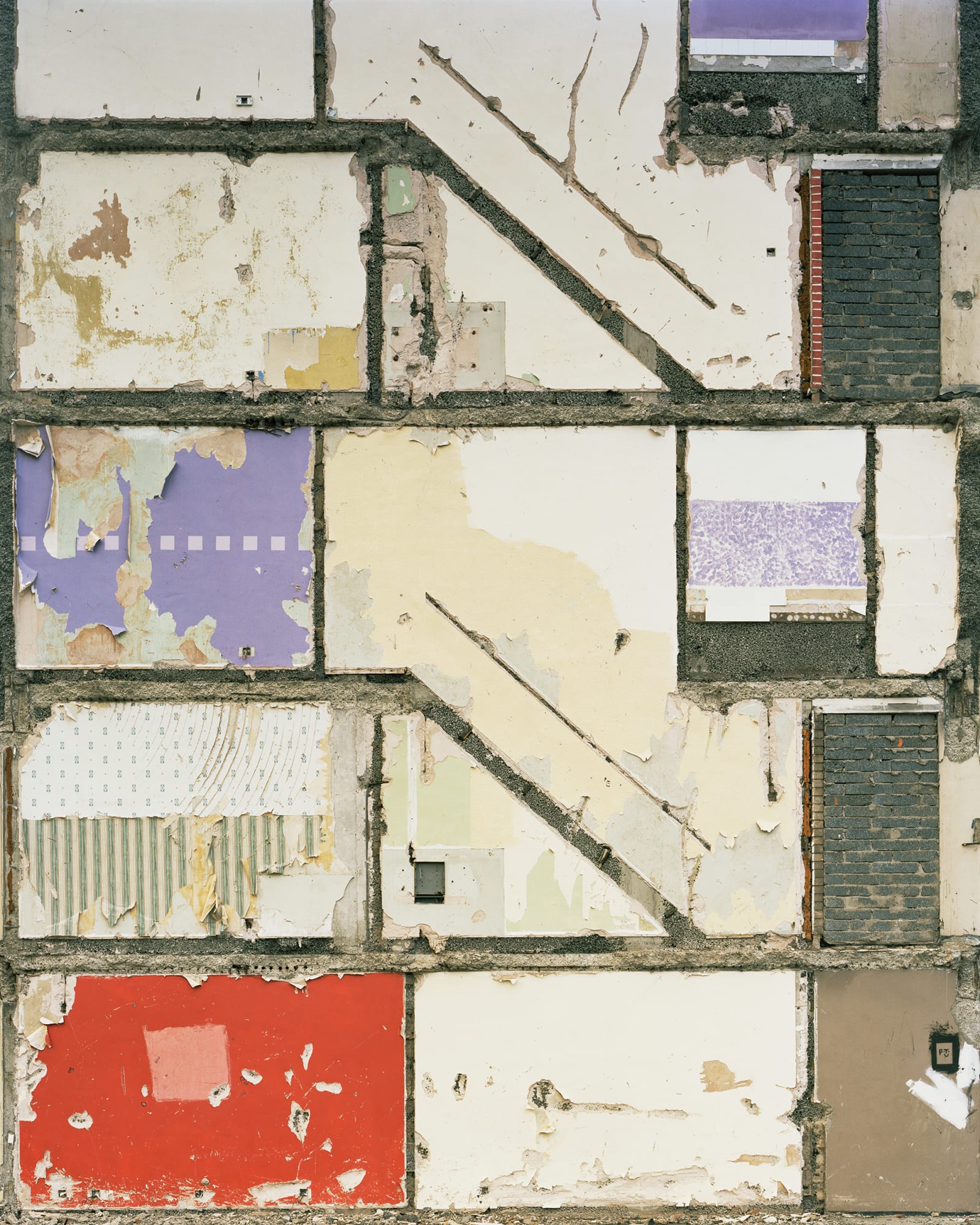

The unabashed pursuit of wealth and self-interest seeming to prove that there really was no such thing as society after all. Housing Estates today have come to be associated with high levels of social stigma; they are seen as places of social exclusion. Homes to the forgotten under-classes, they provide the stage backdrop to our broken society neuroses. As compelling and titillating as any of Hogarth’s scenes. But in the midst of all the media hyperbole and theorising what are these places? Even today are they not people’s homes? Places where children play and belong, where treasured childhood memories are formed however repellant this may seem to middle class observers? What do we see when we look at these images of neglect and decay? How strikingly the physical neglect and abandonment of these homes and proud ambitions seems to reflect the disintegration and malaise of our society as a whole and perhaps even ourselves as individuals.

Text by Richard Healy